Small, modular nuclear reactor designs could be relatively cheap to

build and safe to operate, and there’s plenty of corporate and

government momentum behind a push to develop and license them. But will

they be able to offer power cheap enough to compete with natural gas?

And will they really help revive the moribund nuclear industry in the

United States?

Last year, the U.S. Department of Energy announced that it would

provide $452 million in grants to companies developing small modular

reactors, provided the companies matched the funds (bringing the total

to $900 million). In November it announced the first grant

winner—Babcock & Wilcox, a maker of reactors for nuclear ships and

submarines—and this month it requested applications for a second round

of funding. The program funding is expected to be enough to certify two

or three designs.

The new funding is on top of the hundreds of millions of dollars

Babcock & Wilcox has already spent on developing its 180-megawatt

reactor design, along with a test facility to confirm its computer

models of the reactor. Several other companies have also invested in

small modular reactors, including Holtec, Westinghouse Electric, and

the startup NuScale, which is supported by the engineering firm

Fluor (see “

Small Nukes Get a Boost,” “

Small Nuclear Reactors Get a Customer,” and “

Giant Holes in the Ground”).

The companies are investing in the technology partly in response to

requests from power providers. One utility, Ameren Missouri, the

biggest electricity supplier in that state, is working with

Westinghouse to help in the certification process for that company’s

small reactor design. Ameren is particularly worried about potential

emissions regulations, because it relies on carbon-intensive coal

plants for about 80 percent of its electricity production.

As Ameren anticipates shutting down coal plants, it needs reliable

power to replace the baseload electricity they produce. Solar and wind

power are intermittent, requiring fossil-fuel backup, notes Pat

Cryderman, the manager for nuclear generation development at Ameren.

“You’re really building out twice,” he says. That adds to the costs.

And burning the backup fuel, natural gas, emits carbon dioxide.

Nuclear reactors that generate over 1,000 megawatts each can cost

more than $10 billion to build, an investment that’s extremely risky

for a company whose total assets are only $23 billion. Power plants

based on small modular reactors, which produce roughly 200 to 300

megawatts,

are expected to cost only a few billion dollars, a more manageable investment. “They’re simply more affordable,” says

Robert Rosner,

coauthor of a University of Chicago study of potential costs that the

DOE has drawn on in evaluating the potential of small reactors.

The smaller size has other potential advantages. Siting a large

nuclear power plant can be difficult—it requires, for example, an

emergency planning zone extending 10 miles around the plant, Cryderman

says. That zone could be as small as half a mile for a small modular

reactor—in part because of its size and in part because the reactors

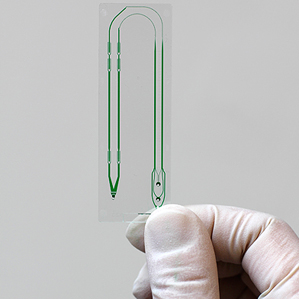

have added design features. For example, while the newest reactors—such

as the Westinghouse AP1000—are designed to keep the fuel cool for

three days without power, small modular reactors can be designed to go

without any power for weeks. He says that if the Nuclear Regulatory

Commission approves a smaller emergency planning zone, that could allow

Ameren to build nuclear power plants at old coal plant sites,

simplifying grid connections and other siting issues.

The smaller size is also an advantage in the United States, where

power demand is growing slowly and many utilities don’t want to add

multiple gigawatts at a time. The modular reactors are expected to take

much less time to build as well, so utilities need to forecast demand

only a few years out rather than more than a decade, Cryderman says.

Yet questions remain about the viability of small nuclear reactors.

While their up-front cost is lower than that of larger reactors, they

might prove to cost more per kilowatt of capacity—and per kilowatt-hour

of power generated.

Nuclear power plants are built large to achieve economies of scale.

“Designers could make the reactors put out more power, but they didn’t

have to increase the capital costs proportionally,” says

John Kelly,

deputy assistant secretary for nuclear reactor technologies at the

Department of Energy. The hope, he says, is that building the reactors

in factories will provide an alternative way to reduce costs—through

mass production. The small reactors are also simpler in some ways,

which can also reduce costs.

But whether those savings will be realized is uncertain. It’s not

clear how many reactors need to be built before the potential savings

from factory production kick in, and whether there will be enough

orders for reactors to hit those numbers. For that to happen, Rosner

suggests, the government may have to be the first customer, buying the

reactors for military bases or government labs.

Even once the final design is approved by the NRC, costs could prove

higher than expected once the plants are actually built. “Part of the

problem when you start in on these things, especially with a new

technology, is that all the news after you begin is bad,” says

Michael Golay, a professor of nuclear science and engineering at MIT. “Things never behave in an optimized fashion.”

Even if small reactors can compete with conventional nuclear power,

they still might not be able to compete with natural-gas power plants,

especially in the United States, where natural gas is cheap (see “

Safer Nuclear Power, at Half the Price”).

Their success will depend on how much utilities think they need to

hedge against a possible rise in natural-gas prices over the lifetime

of a plant—and how much they believe they’ll be required to reduce

carbon dioxide emissions.

“At the end of the day, we’ll build the lowest-cost option for

ratepayers,” Cryderman says. “If it’s too expensive, we won’t build

it.” The challenge, he says, is predicting what the lowest-cost options

will be over the decades new plants will operate.